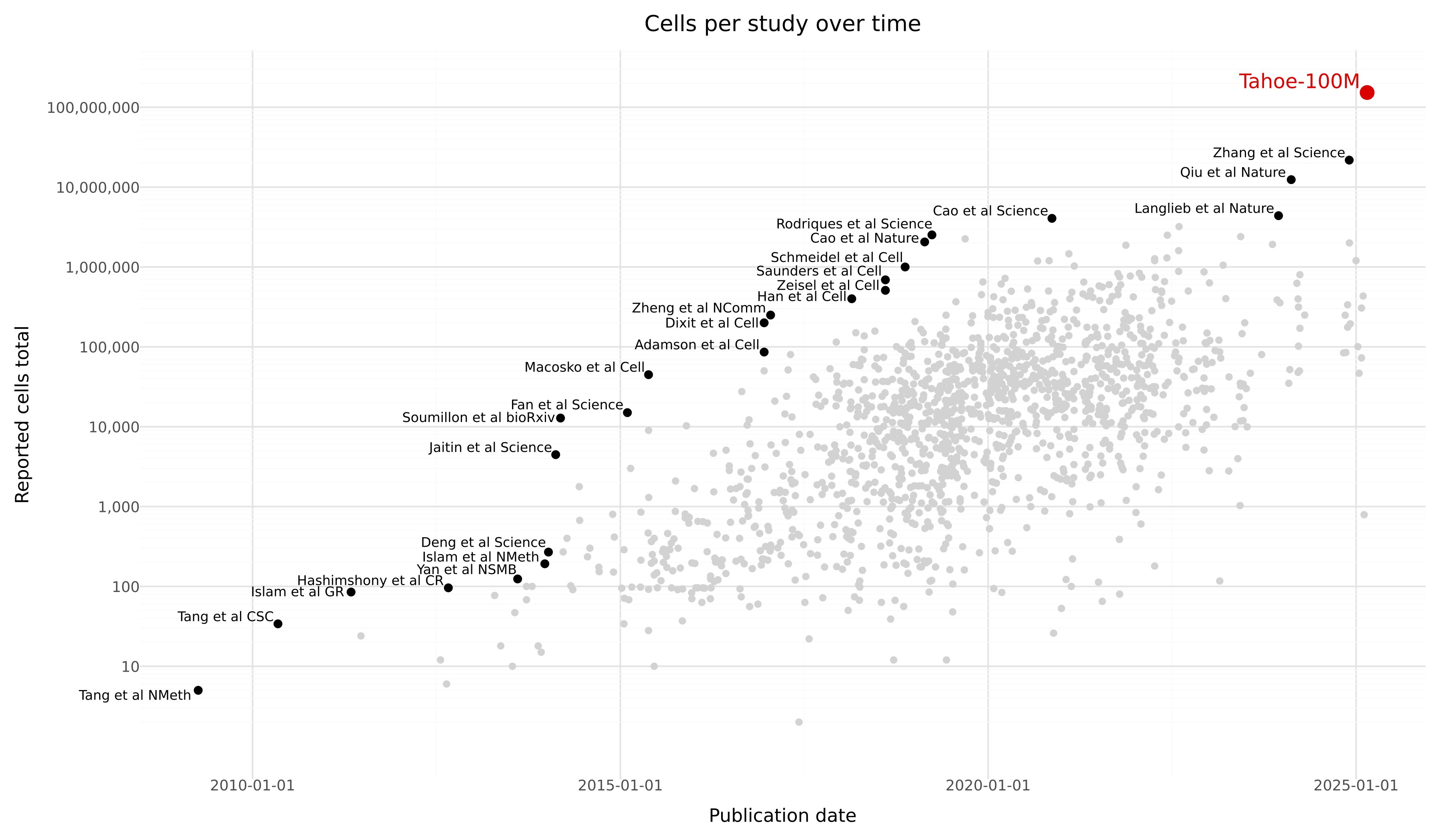

I saw a plot recently, showing the size of scRNA-seq datasets according to release date. Tahoe-100M includes 100M cells and at least looking at this plot, it looks like we have had an exponential increase in the size of the of the largest data sets.

Similar growth in dataset sizes have happened in genomics and elsewhere.

A clear question that arises in this context is then: Can we leverage the growth in data and convert it to value?

For LLMs, the story has been that as compute costs have decreased, we (they) have been able to train on larger datasets, but the main point is that pre-training has allowed for actually useful products like chatbots.

As pre-training has scaled there might have been diminishing returns, and statements by OpenAI regarding GPT-4.5 being the last in the series of large models can be seen as an indication that there has been a limit to pre-training, which has then been taken over by another regime of scaling RL. In any of these cases of scaling, the core is that we have found a way to make the investment in compute worth it, found a way to actually harness the data. Relevant to this question is neural scaling laws

Neural Scaling laws

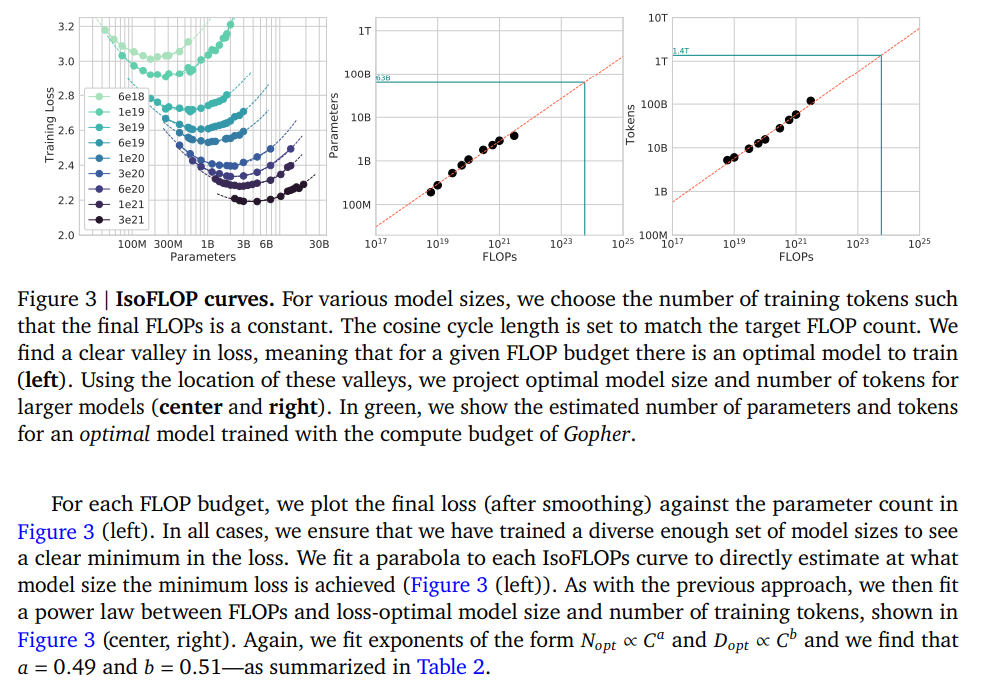

Modern machine learning has entered a paradigm, where scaling laws play an important role both in practice and at the theoretical level. In the regime where we are not bottlenecked by data (though scaling laws do not need this), it has been observed that there are relationships between data size \(D\), number of parameters in model \(P\), and floating points operations \(C\) (compute), that are quite clean. Scaling laws are not restricted to these quantities, and people are actively investigating other relationships and quantities such as batch size and learning rate. One example of an observed scaling law is in the area of compute optimal training \[ L_C = E + c_D D^{-\alpha_D} + c_P P^{-\alpha_P} \]

Consider the case where we are training a generative model \(q(x)\) to minimize cross-entropy \(H(p_{data},q)\) (maximise likelihood of model under data distribution). The cross-entropy can be divided into entropy of the data distribution and the KL-divergence of data distribution to model \[ H(p_{data},q) = H(p_{data}) + KL(p_{data}||q) \] Scaling laws these are based on fitting parametric function to the data we have about training runs of different sizes etc, so there are limits to how seriously we should take a specific formula for scaling laws, but in this picture \(E\) corresponds to the inherent entropy of the data distribution, the noise level.

Looking at the scaling law, in this picture the KL divergence which is always non-negative is being driven to zero as we increase D and N. How fast depends on constants \(\alpha_D\) and \(\alpha_P\). The image is now one where you decide how many FLOPs you are willing to use to train your model, and then determine the optimal number of parameters of your model and how much data you are going to train on.

As has been clear for a long time, this of course ignores the fact that reducing the number of flops needed to reach your desired level of loss is a small part of the picture. After training when you want to make use of the models, bigger models are unwieldy, they require more expensive hardware accelerators to run them on, and ofc they require more flops to run, have higher latency (time to first token generated) and throughput (number of tokens generated per second) than smaller models.

Just as importantly, the loss you reach in pre-training does not directly tell you how well you will perform on a downstream task you care about. After you have pre-trained your model, you want to post-train it, tuning it to do the thing you care about, like being a good chatbot or agent. Only once you have signs that lower loss is robustly correlated with better performance can you justify acquiring the flops and data needed to get a pre-trained model with the low loss that you want.

The value of performance

In the context of LLMs, pre-training data is relatively abundant, even if there is a lot of work to do about ensuring quality of data. In the domain of post-training the abundance of data depends on the task, you might be limited in terms of quality preference data (which response from the chatbot is better, answer A or B?), but in some cases such as software and computer-use agents, given sufficient work, there is the possibility of generating abundant synthetic data, that is directly valuable, by letting agents interact with an environment in a way that closely mimicks the final use case.

It seems that in biology, the picture becomes a bit more muddy. The performance of an LLM on a suite of benchmark can give at least a partial picture of the overall quality, and especially for benchmarks which aim to closely mimick a final use case, it gets close to being a description of the economic value of using the model.

Computational biology methods often are diverse, some methods can give you certain information that can then be used in a variety of ways, and at some point downstream of all these methods being applied, and applied the right way, we might simplistically view it as there being derived some scientific understanding of value or changes of health care outcomes of value.

I am trying to get at some kind of picture where given a certain model with a certain performance on a benchmark, such a model has a certain value for final use cases.

There is an observed market, where chatbot providers provide subscriptions and user’s are paying for access to a model with a certain performance. We are not in a situation where model providers can smoothly trade-off inference cost with performance but this is not unimaginable at all. We could use this to make a simplistic picture of the situation. Assume we simplify performance to a scalar value \(E\) even though it we cannot in practice, then we can now imagine for a fixed performance \(E\) there exist demand and supply curves with equilibrium \(P_*^E\) where \(Q^E_d(P) = Q^E_s(P)\). We are now having a collection of such markets indexed by performance, and a function \(P_*(E)\), being one way of describing the value of performance.

Such a thing is hard to imagine for biology.